“In an article published in 2002 in the journal Physics Letters B, my Ph.D. student Maurizio Piai (now Professor of Physics at Swansea University, Swansea, UK) and I proposed an experiment with reactor neutrinos, emitted copiously by the nuclear reactors in nuclear power plants, to determine the spectrum of masses of neutrinos. The spectrum is one of the fundamental characteristics of the experimentally established three massive neutrinos which is still unknown today,” tells SISSA Professor Serguey Petcov. “In that article we pointed out that this achievement will require, in particular, a very large detector capable of measuring the neutrino energy with unprecedented precision. It seemed that such a detector could never be built so, as a ‘justification’ of our proposal, we wrote at the end of the article: ‘However, as it is well known, "Only those who wager can win."’ In their final statement, Professor Petcov and his collaborator Piai thus quoted the famous “justification” used by Nobel Prize Award Winner Wolfgang Pauli for putting forward the idea of existence of the neutrino. This existence was defined by Pauli himself as “to have a small a priori probability” to be correct.

Further Theoretical Developments

“Nevertheless, in a subsequent study published in Physical Review D with S. Choubey, postdoc at SISSA at the time and now Professor of Physics at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, Sweden, and Piai, we pointed out that such an experiment can also measure with exceptionally high precision—seemingly impossible to be achieved in other experiments—three of the six parameters governing the phenomenon of neutrino oscillations.” These oscillations were hypothesised by Bruno Pontecorvo to exist in 1957 and 1958 and were experimentally observed for the first time in 1998.

From Theory to Reality: The JUNO Experiment

“Against all odds,” continues Serguey Petcov, “the experiment proposed by me and Piai was eventually realized in China by an international collaboration of around 700 physicists, with strong Italian participation.” The experiment is hosted at the Jiangmen Underground Neutrino Observatory (JUNO), built specifically for this purpose in southern China, at a cost of 300 million US dollars.

The JUNO Detector and Infrastructure

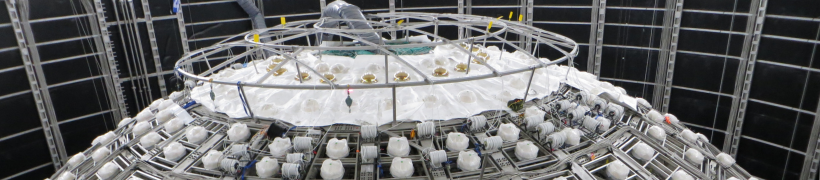

Petcov explains: “It took ten years to construct the neutrino observatory and its detector—a spherical acrylic vessel with a diameter of 35.4 meters, containing 20 kilotons of liquid scintillator (a substance that allows neutrino interactions to be observed) and encased in a stainless-steel structure.” The neutrino observatory is located about 700 meters underground in a cylindrical cavern 49.5 meters in diameter and 71.2 meters high, where the spherical detector is submerged in 35 kilotons of ultra-pure water. Approximately 46,000 photomultipliers are used to detect reactor neutrino interactions and identify background processes that mimic those induced by reactor neutrinos.

First Results and Scientific Impact

Professor Petcov states: “The construction of JUNO was completed on August 26, 2025. On November 19, 2025, after just 59.1 days of data taking, at a press conference in Beijing attended by officials from the Italian INFN and the Italian embassy and consulates in China, the JUNO collaboration announced the first results of the experiment.”These included the measurement of two neutrino oscillation parameters—also responsible for oscillations of neutrinos produced in the Sun—with unprecedented precision, surpassing that achieved by all previous experiments (Super-Kamiokande, SNO, KamLAND), which had collected data over several years. There are already fourteen publications analysing the particle-physics implications of JUNO results.

Future Prospects and Scientific Goals

“These are only the first of many remarkable results expected from the JUNO experiment, which has unique physics capabilities,” Petcov explains. These include determining the neutrino mass spectrum, measuring three neutrino oscillation parameters with exceptional precision, studying oscillations of reactor, solar, and atmospheric neutrinos, detecting neutrinos from a supernova explosion and the diffuse supernova neutrino background, measuring the flux of geoneutrinos, searching for proton decay, and probing physics beyond the Standard Model. The JUNO experiment has reported impressive new results after only 59.1 days of data taking, achieving a factor of 1.6 improvement in the precision of solar neutrino oscillation parameters compared with previous experiments.

Conclusion: The Value of Scientific Risk

With its rich physics programme and unique detector capabilities, JUNO is set to be a leading experiment in neutrino and particle physics for the next 20 years and possibly beyond 2045.Professor Petcov concludes: “JUNO will advance our knowledge in the fields of particle and astroparticle physics, about the Earth, the Sun, and possibly about the stars. The example of the idea of JUNO is another confirmation that in physics—and not only—one should not be shy to ‘wager’ when hitting upon a seemingly ‘impossible’ idea with far-reaching or breakthrough implications.”